Posted March 30th 2020

Mae cynnwys hwn ar gael yn Saesneg yn unig

In the last decade, there has been a resurgence in research on magic mushrooms and their potential therapeutic use.

Psilocybin mushrooms are known for their intense psychedelic effects. Psilocybin can be found in around 200 naturally occurring mushroom species and acts as a serotonin receptor agonist and a pro-drug, meaning it is converted in the body to psilocin, a chemical with psychoactive properties.

Serotonin is an important chemical and neurotransmitter in the human body. It is believed to help regulate mood and social behaviour, appetite and digestion, sleep, memory, and sexual desire and function…

Ancient History

Some believe the origin of magic mushrooms goes back thousands of years. Symbols, statues and paintings from Native American cultures may indicate the use of psilocybin mushrooms, and that they had a place in religious rituals.

The Aztecs seemed to use a substance called “teonanacatl”, which roughly translates to “Flesh of the Gods”; many believe this refers to psilocybin mushrooms. None of this evidence is definitive, however, there is confirmed use of these mushrooms in religious settings among some contemporary tribes of indigenous peoples in Central America.

More recently…

It was not until the 1950s that the Western world was introduced to psilocybin. R. Gordan Wasson and Roger Heim discovered psilocybin mushrooms whilst on expedition in Mexico, where they witnessed and partook in a ceremony from the Mazatec tribe (an indigenous people from the Oaxaca region of Southern Mexico). Wasson returned and wrote an article on his findings, which was published in 1957 in ‘Life’ magazine named ‘Seeking the Magic Mushroom’. Since this article, the name ‘Magic Mushroom’ is commonly used when referring to mushrooms with psychoactive properties.

Heim and Wasson had returned from Mexico with a sample of psychedelic mushrooms, and they enlisted the help of Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman (now known as being the “father” of LSD) who isolated and extracted psilocin and psilocybin from the mushroom.

Soon magic mushrooms started to be used recreationally in Western society, with people desiring their strong psychedelic effects.

In the 1960s they became associated with counterculture and the hippie movement, with some considering them to be the gateway to spirituality. In response to this, the 1970s brought a ban on psilocybin and magic mushrooms with the classification as a Class A substance on the Controlled Substances Act, where they remain to the present day.

Today, magic mushrooms are still used illegally, but in the last decade there has been a resurgence of research into whether psilocybin can have positive implications in mental health; so much so, that in 2018 the FDA designated psilocybin therapy as a ‘Breakthrough Therapy’, an action that accelerates the process of drug development and review.

What does the research say?

A small number of studies have been conducted trialling psilocybin on patients with treatment-resistant depression. A person may be defined as having treatment-resistant depression if their symptoms of major-depressive disorder do not subside with attempted treatment from two different classes of antidepressants.

In a small-scale feasibility study, patients with severe treatment-resistant major depression received two doses of psilocybin, seven days apart. Patients felt acute psychedelic effects between 30 and 60 minutes after dosing, with effects subsiding to negligible levels after six hours.

The results demonstrated that after one week, as well as after three months, depression scores significantly decreased, with the majority experiencing reduced depression severity after three months.

Although exciting, these findings must be taken with a pinch of salt as this was only a small study with a small sample size.

However, further research has been conducted with similar findings of efficacy. In the Johns Hopkins psilocybin research project they found that 80% of healthy volunteers that returned a month after having one or two doses of psilocybin reported that the experience of taking the drug was in their top five meaningful experiences they’d ever had. Around 90% reported increased positive mood and greater life satisfaction.

Further studies of psilocybin have shown that for those with anxiety and patients with life-threatening cancer, the drug produced immediate, substantial and sustained improvements in anxiety and depression.

At a six-month follow-up, psilocybin was associated with enduring anti-depressant effects and sustained benefits in existential distress and quality of life.

The presented findings certainly warrant the funding for larger-scale studies. However, it should be noted that there is a need for much more research before making any great assumptions regarding the future of psilocybin in a clinical setting.

What does taking part involve?

Taking part typically involves taking a dose of psilocybin in a controlled environment which has been decorated to feel warm and comfortable for the participant.

Before the treatment, a medical professional will make sure to prepare the patient as much as they can for what’s to come; it’s important that the patient feels open-minded and ready to embrace the experience.

During the treatment, patients are given an eye mask and offered some music to listen to. Therapists are constantly present to monitor the participant and the participants should be very familiar with the therapists so that they are completely at ease during the treatment.

How do patients report feeling?

The nature of peoples’ experience on magic mushrooms are very subjective and can vary greatly. Common effects include warping of time and space perception, hallucinations, and a distorted view of the world, with changes to colours, objects and sounds commonly reported. Following the treatment, some patients have reported feeling like the “fog has lifted” inside their head, a kind of mental reboot, like “turning the lights on in a dark house”. Some individuals report a shift in their brain from avoiding their emotions to accepting them, and a greater sense of connectivity between their thoughts and feelings.

It’s important to note that not everybody will have a positive experience whilst under the influence of the drug, as the effects differ depending on the surroundings and the people you are with. This is why it’s so important that, in a clinical setting, the patient is totally comfortable with the researcher and that the surroundings make the patient feel at ease.

How does it work?

For all the promise of psilocybin for mental health treatment, very little is known about its exact therapeutic mechanisms. In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of those with depression, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) has been shown to be hyperactive, and effective treatment of depression has shown to normalise this. Carhart-Harris (2017) found that psilocybin consistently deactivated the mPFC.

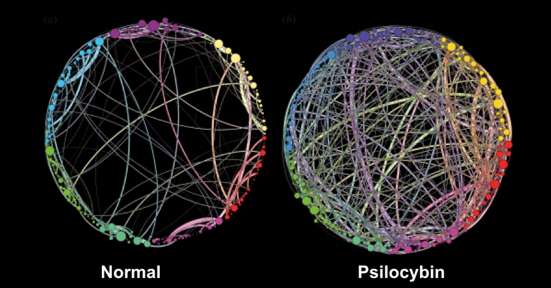

The default mode network (DMN) is a loose connection of brain regions that communicate together when performing everyday tasks. Hyperactivity in certain areas of the DMN has been correlated with excessive rumination in those with severe depression.

Brain scans of those under the influence of psilocybin have shown increased brain connectivity in regions that may not have interacted since the patient was a child.

As a child there is greater connectivity in the brain, somewhat explaining the emotional sensitivity and hyper-imagination associated with children.

Similar effects are associated with psychedelics, psilocybin has been proposed to reduce the activity in the DMN, supposedly turning the DMN off and then back on again. fMRIs also show looser connections between brain networks after taking psilocybin, it’s suggested that these networks then reintegrate; Carhart-Harris (2017) proposes a ‘reset’ therapeutic mechanism. This so-called ‘resetting’ of the brain may explain how psychedelics can help overcome dysfunctional pathways and subsequently help patients break compulsive negative thought patterns and behaviours.

There is still a need for much more research to know exactly how psilocybin works as a therapeutic treatment.

What’s next?

Dr Robin Carhart-Harris is leading one of the first trials to test how therapy using psilocybin mushrooms compares to leading antidepressants. This is one of many studies planned at the new Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London.

He believes that psychedelic therapy will be licensed sometime in the next five to ten years, but there is still a long way to go. This presents its own issues, if psilocybin is found to be more effective than current antidepressant medication such as SSRIs, big pharmaceutical companies are likely to become involved.

In the US, a pharmaceutical company named Compass Pathways are conducting a phase two clinical trial (trials testing efficacy), with 216 participants across North America and Europe, making it the largest clinical trial to date.

It’s suggested that if these trials are successful, it could lead to psilocybin therapy becoming legal in the US by 2021. However, there are some concerns regarding the intentions of Compass Pathways; they have patented a synthetic manufacturing process of psilocybin, and some believe that they are trying to corner the psilocybin market and prevent others from researching it.

Aside from this, research into psilocybin is ongoing and very exciting, with promising therapeutic efficacy.

Will we soon follow in the footsteps of our ancestors and harness the beneficial effects of psychedelics? Only time will tell.

Read more

- NCMH blog – The psychedelic renaissance – NCMH placement student, Sam, takes a look at MDMA assisted therapy for PTSD.

- Conditions we study – Depression